It’s the first e-journal of 2020. In this blog, I will be answering TOK questions that Mr Kichan gave us. TOK stands for Theory of Knowledge and it basically questions everything about life and your existence (just like how I’m questioning my life choices being in MAAHL). It questions on how we know the knowledge that we know. So let’s get started.

Credit: quick meme

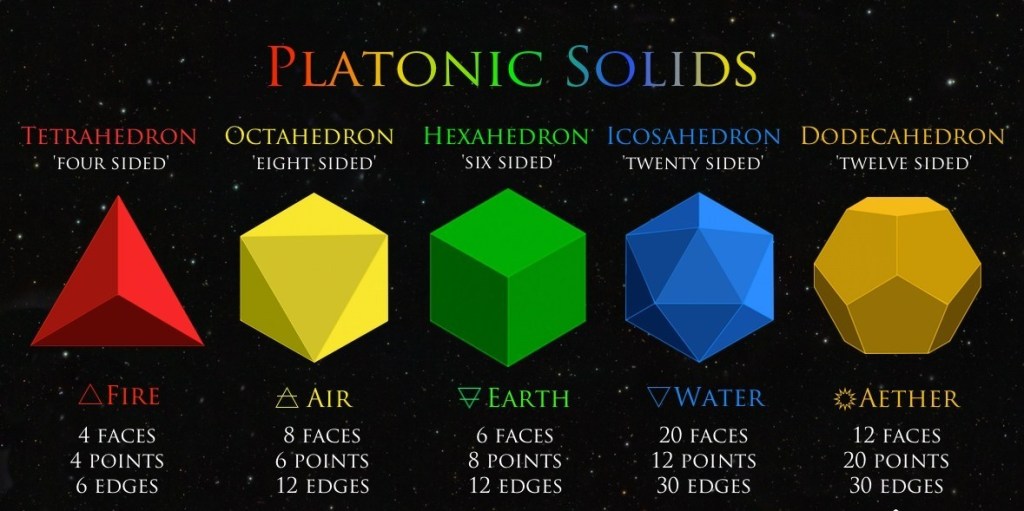

1. What are the platonic solids and why are they an important part of the language of math?

The platonic solids are solids named after an ancient Greek philosopher named Plato. Platonic solids are regular polyhedra, which is a three dimensional (3D) figures where each of the solid’s face is the same regular polygon (polygons whose angles and sides are all equal). And at each vertex, an equal number of polygons would meet. They are unique because no matter the direction, these solids would be perfectly symmetrical.

There are a total of 5 different platonic solids. And each of these solids correspond to a specific element. They are:

Credit: Joedubs

The platonic solids are important to the language of maths because of their significance in history. Mathematicians have known about the platonic solids for over 2,000 years now. And these solids have played a vital part in the development of not only philosophy, but also science in the Western culture.

According to Plato’s view, the platonic solids are building blocks of the whole physical universe, including matters that are both organic and inorganic. And the platonic solids have uses ranging from architecture to technology. These solids and Plato’s ideas have had an influence in various cosmological thinking, including Kepler’s discoveries. Pythagorean-Platonic ideas inspired Kepler’s discoveries in the field of astronomy regarding geometry’s cosmic significance. Platonic geometry also has a prominent feature role in the work of Fuller, an American philosopher and inventor.

Hence, the platonic solids are a crucial part of the math language because of its significance and its wide range of uses. But more important, it led to various discoveries that otherwise may not have been discovered without these solids. (So thank you platonic solids.. yay :D)

2. To what extent do instinct and reason create knowledge? Do different geometries (Euclidean and non-Euclidean) refer to or describe different worlds?

Instinct is the gut feeling that is built into every human and creature on this earth. Everybody’s instinct is different. Based on their instincts, two people can react to the same situation in different ways. And reason is when there is a reason that supports and backs up why one does what they do. And how do these two create knowledge?

For example, when two people sees a dog. One of their instinct would be to run away from the dog, but the other person’s instinct could be to approach the dog and pet it. These actions were done subconsciously by instinct as it was essentially their reflex action, how their body reacted to the situation even if they may not have realized it. It was done without reason. But if they acted upon reason, they may have just walked pass the dog calmly. This action was done based on a reason, which was that they didn’t want to spook the dog, as spooking the dog may result in them getting bitten. However, even though reason and intuition can act separately, they can act together as well. Like another two people, one may have ran away from the dog because they previously have had a bad encounter with dogs, such as getting bitten, and the other may have approached it because they have had a good encounter with dogs like previously owning a dog. These are actions were done with the combination of instincts and reasons. Even though the action was have been instinctual, they each have a reason on why they did those actions, reacted the way they did.

So how does this correlate with knowledge? Let’s say one thought of an idea and they want to explore more on this idea. They will try to find out more about this idea. That first step was done by intuition as they felt as if it was a good first step, a good starting point into getting answers or finding discoveries regarding their idea. And from there, they found more information that led to them doing more steps and conducting further research on their idea because they had a reason, a reason that was obtained from the information they read, creating knowledge. Similar with the dog analogy, knowledge is created best when instincts and reasons are combined together. You can’t find reasons without having that initial instinct, the instinct that sparked curiosity that caused us to want to find answers and reasons because humans are naturally curious. You cannot obtain the best knowledge if it is solely based on instincts, similarly with reason. One will not want to seek for reasons if they don’t have that natural curious instinct.

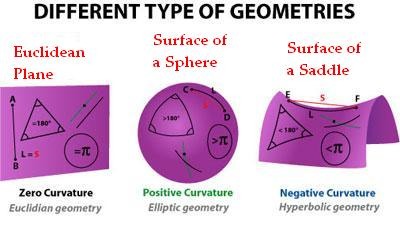

Euclidean geometry was named after a Greek mathematician whose name was Euclid. Euclidean geometry is the geometry that we have all been learning in secondary, the ones about planes and solid geometry. The fancier description of Euclidean geometry is the study of figures (plane and solids) based on axioms (his five postulates) that eventually led to theorems. Axioms are basically the written rule that are used to make theorems.

What are Euclid’s five postulates? They are (quoted from Euclid’s book):

- A straight line segment can be drawn joining any two points.

- Any straight line segment can be extended indefinitely in a straight line.

- Given any straight line segment, a circle can be drawn having the segment as radius and one endpoint as center.

- All right angles are congruent.

- If two lines are drawn which intersect a third in such a way that the sum of the inner angles on one side is less than two right angles, then the two lines inevitably must intersect each other on that side if extended far enough. This postulate is equivalent to what is known as the parallel postulate.

Non-Euclidean geometry is the rest of the geometry that doesn’t fall or belong under Euclidean geometry. There are two types of non-euclidean geometry – hyperbolic geometry and spherical geometry. Hyperbolic geometry is a space that is “curved” and spherical geometry is plane geometry on a sphere’s surface.

Credit: Nebi Caka on Research Gata

So do Euclidean geometry and Non-Euclidean geometry refer or belong in the same world? I believe that to some extent, they do refer to the same world, but to another extent, they do not.

I think that when Euclidean geometry and Non-Euclidean geometry is mentioned, they refer to and belong to the same world in some ways. In what sense? They both refer to the big world of mathematics and a slightly smaller world of geometry. In other words, they both belong to mathematics, and they both belong to geometry (they both have geometry in their names after all right?).

But on the other hand, they may not refer to the same world. They belong in two different worlds under geometry. So let’s say geometry is a big island, and Euclidean geometry and Non-Euclidean geometry are two different parts of the big island of geometry. Two different parts with very different culture and ways of living.

In conclusion, I feel like Euclidean and Non-Euclidean geometry belong in the same world in the sense that they are both under mathematics and geometry, but is also different as they are two different worlds within the world of geometry.

3. Is it ethical that Pythagoras gave his name to a theorem that may not have been his own creation?

In order to completely grasp and answer the question, I believe that it is important to know about the brief history of mathematics.

According to Microsoft Encarta Encyclopedia, the definition of mathematics is “the study of relationships among quantities, magnitudes and properties, and also of the logical operations by which unknown quantities, magnitudes, and properties may be deduced”.

The origin of mathematics can be traced back to pre-historic times Mesopotamia (Babylonia and Sumer) and Ancient Egypt. Though we can infer, no one is completely sure of the origin as there is no proof regarding the first use of mathematic’s origin.

In early mathematics, it is said that there is a huge chance that Babylonia and Ancient Egypt were the two that made the biggest advancement due to various reasons including the age of their existence, accessibility to resources and population. In this blog, I will be focusing more on the Mesopotamia.

Even back then, Mesopotamia had a numerical system. The Babylonians utilized symbols representing singles, tens, and hundred to write down numbers, known as Babylonian cuneiform numeral. Because of this, they were able to comfortably handle large numbers and allowed all major arithmetical functions to be performed. However, no evidences show that they utilize zero and more general fractions. Other than that, the Sumerians utilized a base 60 counting system, called the sexagesimal system. This system was utilized for weights and measures, astronomy, and mathematical functions’ development.

Source: Pinterest

The babylonians were also able to extract square roots, solve linear systems, studied circular measurement, and were even able to solve cubic equations, through the help of tables. However, their geometry were occasionally incorrect. The biggest thing I found out that in some ways amazed me was that they were already working with Pythagorean triples. Yet the Babylonians never knew Pythagoras.

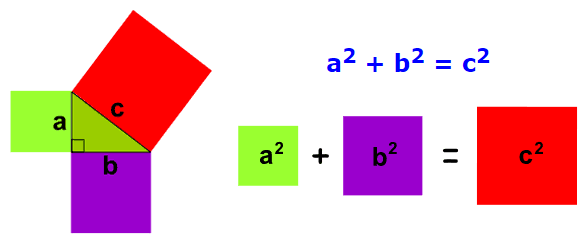

Pythagoras is a Greek philosopher born around 569 BC. He is famously known for the Pythagoras Theorem. The Pythagoras Theorem states that in a right angled triangle, the square of hypotenuse (the longest side and the side opposite the right angle) is equal of the sum of the squares of the triangle’s other two sides.

Credit: Maths is Fun

However, it was said that Pythagoras did not write any of his own report and that his views were derived from others. This could be held true as within Pythagoras’ society, there was a strict secrecy and members of the society had shared ideas and intellectual discoveries with one another without giving individuals credit. Other than that, there was no extensive account of Pythagoras, and the first detailed account regarding him only survived in fragments. All of these led to some speculations on whether this theorem was the creation of Pythagoras or not.

A Babylonian tablet, known as Plimpton 322, was recovered somewhere in a desert in Iraq (Babylonia is now known as Iraq). This tablet was said to be written around 1800 BCE. This tablet has a table that consist of a part of the Pythagorean triplet list. (More information on this can be read on https://www.math.ubc.ca/~cass/courses/m446-03/pl322/pl322.html.)

To some extent, I don’t think it is acceptable because taking credits for other’s work is not only unacceptable, but also unethical as that person worked hard for his/her own creation and somebody else took it. It is the same idea as plagiarism. We aren’t allowed to take somebody else’s ideas and pretend that it is our own ideas.

However, Pythagoras may not have been the one who gave his name to this theorem. Maybe somebody named this theorem after Pythagoras after he died without his knowledge. If this was the case, how would he have known? He couldn’t have changed it. In this scenario, I think that it is ethical as he wasn’t trying to take all the credits for the creation but rather, someone gave him credit without him asking for it and it isn’t his fault.

But who do we give credit to? Like in this case, who do we give credit to regarding Pythagoras’ Theorem? The babylonians or Pythagoras? Or somebody else? The babylonians may have had the idea of Pythagoras’ Theorem through Pythagoras triples, but they never knew him or his theorem. They may have knew it accidentally or unintentionally, without knowing that it could’ve been another theorem. But how are we sure that they were the first ones to utilize this? What if there was someone before the Babylonians that knew about the Pythagorean theorem or triple but it was never written down? Or maybe it was written down, but all the evidences were either undiscovered or lost or destroyed? Do we give credit to the person who created the evidence that was found? So let’s say Pythagoras did create this theorem, are we supposed to give him the credit even though he technically wasn’t the first one to know about it or had the idea? But Pythagoras never knew the Babylonians, so he couldn’t have known about it or took the information from them. How do we give credit to an idea or thought that isn’t written down or have no physical proof? How do we know that an idea and thought is original to somebody? Because a couple people may have the same thought or idea, so who do we give credit to? This is the same case with Thales, where it is said that he was given credit to stuff he didn’t do.

Credit: giphy

In conclusion, I think that it may or may not be ethical depending on how it is looked at. And the issue on giving credit is still in question because how does one give credit to an idea or thought that wasn’t written down or mentioned? But if a person stated an idea or thought, how do we know that that person is the first one to think of that idea of thought? I think that questions will just lead to more questions and we will never know, even if we have a time machine and can travel back in time.

To wrap this blog up – TOK makes you question everything about life (like I mentioned above). It questions how we know what we know. To future IBDP students, good luck with TOK 😉 Because this will be the answer you will get in TOK:

Credit: quick meme

Sources:

- https://www.mathsisfun.com/platonic_solids.html

- https://joedubs.com/the-platonic-and-pythagorean-solids/platonic-solid-chart-top/

- https://science.jrank.org/pages/5340/Platonic-Solids.html

- https://www.gaia.com/article/platonic-solids

- https://www.comsol.com/blogs/how-to-use-the-platonic-solids-as-geometry-parts-in-comsol/

- https://www.cs.unm.edu/~joel/NonEuclid/noneuclidean.html

- https://www.britannica.com/science/Euclidean-geometry

- https://www.britannica.com/science/non-Euclidean-geometry

- https://www.mathsisfun.com/pythagoras.html

- https://www.mathopenref.com/pythagoras.html

- https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/pythagoras/#PytQue

- http://mathworld.wolfram.com/EuclidsPostulates.html

- https://www.researchgate.net/post/Is_there_a_triangle_which_has_sum_of_three_angles_not_equal_to_180_degree2

- http://www.malinc.se/noneuclidean/en/

- http://www.quickmeme.com/p/3w46no

- https://www.storyofmathematics.com/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Babylonian_cuneiform_numerals

- https://www.pinterest.es/pin/455989530993384575/?lp=true

- https://www.math.tamu.edu/~dallen/masters/egypt_babylon/babylon.pdf

- https://explorable.com/babylonian-mathematics

- https://www.math.ubc.ca/~cass/courses/m446-03/pl322/pl322.html

- https://giphy.com/reactions/featured/mind-blown

- https://lh3.googleusercontent.com/proxy/2tIFhPEWB13J9767ddLDOfn8rsxNU2yAiaN1HzNBhL80ra_qhOhScxb3h_3OO5wH_Z2HRPMncrVHgQ7X9InvM59rg90WABfKsRV802mJIDLHyXR2qPGf-kZdAb9xmJpB_hN9wLH6CUXcrdB1g2K_UMoa9lpkLm0p_QA